The Fragrance of the Blessed Realm

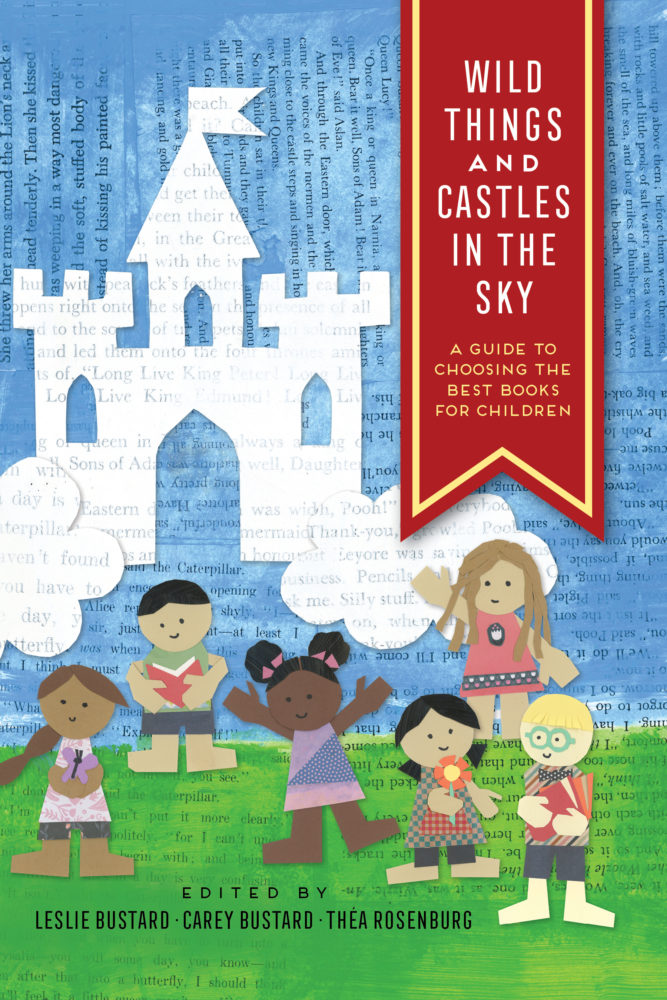

WILD THINGS AND CASTLES IN THE SKY: A GUIDE TO CHOOSING THE BEST BOOKS FOR CHILDREN

Wild Things and Castles in the Sky: A Guide to Choosing the Best Books for Children gives the reader over 40 essays that examine specific types of children’s books and offer suggestions in each category. Among the topics covered are: imagination, faith, classic literature, middle school books, race, fantasy, contemporary children’s books, Shakespeare, art history, Newberry books, young adult novels, poetry, and more. Curated and edited by Leslie and Carey Bustard with Théa Rosenburg (a mother-daughter team and a children’s books blogger), Wild Things and Castles in the Sky will encourage and envision parents, grandparents, teachers, and friends—to know the power of a good story and to share it with a child they love.

In Philippians 4, the Apostle Paul calls us to think on things that are “commendable” or “of good report.” Wild Things and Castles in the Sky is just such a book. Filled with essays to help you find other commendable books, it also manages to be commendable in itself, replete with wonder, beauty, and inspiration. But I suppose the greatest commendation I can offer is to simply tell you that my book budget grew ten fold with the reading of it.

—Hannah Anderson, author of All That’s Good: Recovering the Lost Art of Discernment

The Fragrance of the Blessed Realm (first published by Square Halo Books in Wild Things and Castles in the Sky

From where I sit writing to you now, I can hear (but cannot see) two, possibly three, windchimes perfuming the air with their music. The wind is filtering through the thick, pale green leaves of an old maple that hunches over my shoul- der as I lean back in a chair by the patio table of my friends the Moons. It’s easy to imagine how Isaiah could say the trees “clap their hands” (Isa. 55:12); the trees make myriad applause above me as they are blessed by the breeze’s breathing. The wind and the leaves are filled like a glass with warm autumn sunlight, and the wavering, water-like overtones of the chimes seem to wing their song through and above everything all at once, as if the beauty of some other world (or some unseen aspect of this one) presides over all of this, singing into it its life, like light beyond the spectrum of human sight making its Presence felt from someplace off-stage.

The chimes I speak of are invisible to me. I hear them; I don’t know where they are. But have you ever broken the rind of a nutmeg seed on a grater and breathed in its fragrance? It’s like that. The fragrance that escapes out of that little spice-stone seems almost rather to have escaped into this world from another blessed realm. The simple action of rubbing the nutmeg wakes a kind of communication between a world that looks like a hard, dry seed and a world spilling over with the very fragrance of life and warmth.

Can you think of times you have experienced the beautiful fragrance of the blessed realm “breaking into” this world? Is there a certain place here where the reality of God’s goodness becomes palpable, the Kingdom seems truly to be “at hand”? Is there a friend in whose presence you find your shoulders relaxing and your breath deepening, though you hadn’t known you were anxious before? Perhaps there is music that, to your surprise, puts a lump in your throat?

Maybe a there’s a story that you’ve heard

That opens up an aching in your heart

Where something like a light behind a door

Has made it through the cracks to where you are?

There’s a lump in your throat,

And the tears come to your surprise;

Like there’s someplace that you belong

With someone who loved you all along.

There are many ways to “break the rind of the nutmeg,” so to speak, and one of the most powerful for me has been story. As a child, J.R.R. Tolkien’s storytelling both took me into another world and brought me back to this one with renewed vision, capable of detecting “heaven in ordinary,” as the poet George Herbert puts it. As a late teen, my youth minister introduced me to G.K. Chesterton. I’ve read and reread his Orthodoxy over the years, particularly stopping to linger over the chapter “The Ethics of Elfland.” If ever there was a chapter to shake the dust from an unused imagination and re-enchant the heart!

That same youth minister one day handed me his copy of George MacDonald’s strange little fiction book Lilith to read. I was transported. And bewildered. I really wasn’t at all sure what had taken place, in the book or in myself. But some great hand had indeed swept across the dust-crusted glass in the picture frame, and I began to see that new color, form, and images had lain underneath all the while. (Or, as a child of the 80s, I can’t help but think of the Goonies finding a fabled treasure map tucked beneath a painting in the attic.)

So, I find myself on edge for those clues strewn about this world; where might I find a loose panel opening into a passageway, or feel fur coats in a wardrobe translating into fir trees in a wood? There is a liturgy that says, “All of us go down to the dust, but even at the grave we make our song.” That seems to me to get at the experience we search for—to enter like the child Lucy Pevensie into the wooden casket, to change our garment, and wake walking in another world—but in that case, a world where it is always Christmas.

Occasionally, we get those intimations in this world. Christmas itself arrives through the cracks like “light behind a door,” doesn’t it? And one of the effects is that the “goodwill toward mankind” that the angels herald to the shepherds of Bethlehem really does seem to be coaxed to the surface of our own hearts. God has smiled upon us, come to visit as Emmanuel, and it is hard not to offer God’s own goodwill in return. Not the small cynical smirk of commercialism, but the great-hearted gladness of grace that marks that season in spite of its secularization. (And Christmas is certainly a time to grate a little nutmeg atop your eggnog.)

Now, Christmas is a high point of the in-breaking of God’s presence, but if Tolkien, Chesterton, and MacDonald are correct, it’s not meant to be exceptional, but indicative. The realities indicated by the Scriptures fall like snowflakes, each unique, to dissolve into the material of this world and spring up in endless ways through poems, songs, stories, and so on, which draw us toward and into the beauty, goodness, and truth of the Life of the Trinity.

Now, all of that is a big approach to a little book I’ve been rereading for the third or fourth time called Sir Gibbie, by George MacDonald. Since we are looking at books for children, it may help to know that there are a few different versions: the original, due to length and frequent passages written in dialect, isn’t the best place to start for a child. Rediscovering that original version as an adult after having grown up with an abridged version would be fun, I think. I’m recommending Michael Phillips’s version, Wee Sir Gibbie of the Highlands, which has been edited for young readers.

Sir Gibbie is a realistic novel set in the Scottish Highlands, and it follows a mute little boy who, soon after being orphaned, witnesses a murder and runs away from the city. He winds up on the estate and farm of the local Laird (roughly the Scottish equivalent of an English Lord, or landowner). He’s run out of there and finds refuge with an older peasant couple, Robert and Janet Grant, in their cottage in the mountains. Without giving away the story, the Grants raise him in dignified poverty, introduce him to life in Jesus, and eventually learn more about his true identity.

Just the action, mystery, and fun of the story would be enough to recommend it, I imagine but, in this story MacDonald has a way of “breaking the rind” of the nutmeg for us. To begin with, Gibbie’s character in this story is an experiment in purity and innocence. It’s almost as if MacDonald asked, “What if someone could retain the innocence of childlikeness as they grew? What would a story about someone pure look like?” Gibbie is often described in angelic and other- worldly terms with great affection. Put simply, he is good.

One of the great effects this book has on me, personally, is that it makes me desire goodness in myself. It makes goodness immanently attractive, which is a difficult thing to do in storytelling. You may have noticed how easy it is to make bad- ness entertaining in our media? It’s easy to take the dried brown stone of nutmeg and throw it at someone, but MacDonald gently scratches its surface to release the delicious fragrance of goodness. We find in Gibbie that the human personality can do so much more than entertain through brashness: it can nourish and delight through goodness and gentleness. With Gibbie, MacDonald allows that warm fragrance of God’s goodwill toward mankind to break in on our imaginations—to populate it with new images of how we might live beautifully through goodness.

And Gibbie is not the only character to inspire us in this way: Janet and Robert exhibit faithfulness to one another, joy and contentment in poverty, tenderness, and love toward their children and the orphan Gibbie, and the un- pretentious wisdom that comes from real and regular contact with a living Jesus.

One of the interesting ways that MacDonald affects goodness through Gibbie is by making him mute. Late in the story, Gibbie learns to read, write, and sign, but the majority of the time the only language at his command is action. He offers the honest gift of his presence, marked most often by his ready, warm smile and free laughter. Besides that, he serves others. He is joyful and careful with everyone he comes into contact with. MacDonald gives us a character who is literally incapable of “lip-service” to the gospel; Gibbie’s faith skips happily over speech directly into loving deeds.

Recently, my friends the Moons and I watched a movie about Fred Rogers of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Fred Rogers might be a modern-day Sir Gibbie in some ways. I was reminded of a quote from one of Rogers’s speeches, where he described a news story of a young boy who kidnapped another child. When the boy was asked why he did it, he said he saw it on television and thought it was something interesting to try. Rogers went on to say,

Life isn’t cheap. It’s the greatest mystery of any millennium, and television needs to do all it can to broadcast that—to show and tell what the good in life is all about.

But how do we make goodness attractive? By doing whatever we can to bring courage to those whose lives move near our own—by treating our neighbor at least as well as we treat ourselves and allowing that to inform everything we produce. We all have only one life to live on Earth. And through television, we have the choice of encouraging others to demean this life or to cherish it in creative, imaginative ways.

The imagination is like a corkboard where we pin images we pick up along the way in life. And it’s where we go looking for pictures of how our own lives might possibly look. Those images that populate our imaginations have a lot to do with what we acquire a taste for as well, whether it’s goodness or badness.

As Fred Rogers indicates, it is very important to collect good images to pin on our corkboard, because they form a taste for the things of God and they bring good choices within reach for us. In other words, if our imagination is atrophied or populated by devastating images, we might say, “I can’t imagine myself being loved or loving well.” On the other hand, the more good stories, characters, music, and beautiful experiences we internalize, the greater our resource for godly feeling and action becomes (Phil. 4:8).

Reading Sir Gibbie helps populate my imagination with goodness. When I go to consult my imaginative corkboard for images of how I might feel and act, I find Gibbie warmly smiling, silently serving, eagerly attending his friend Donal’s poetry recitations, gladly freeing an enemy who did him great violence, and embracing the poor.

Often in MacDonald’s storytelling, he shows the interpenetration of heaven and earth—how “Earth’s crammed with heaven,”3 as the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning says. In Sir Gibbie, the music of those invisible wind chimes seems always to be present, as is the fragrance of Christ humbly making its way through the world like a ragged, mute orphan boy who carries the goodwill of God in his smile.

A Prayer for Little Readers (and Big Ones, too)

Dear Lord, this world has a story, and you are its Storyteller. We, your children, are listening for your Word, learning your voice, and looking for your character everywhere. We look and listen through the beauty of the created world you have so astonishingly given. We sense the presence of the world’s Author when we pay close attention to what Jesus has done and revealed of God in the Scriptures. And we joyfully, eagerly search the pages of our favorite myths, tales, stories and poems for the lingering fragrance of the blessed realm, your Kingdom, Lord God, where you will settle us in your family forever. There, “at last [we will be] beginning Chapter One of the Great Story which no one on earth has read: which goes on forever: in which every chapter is better than the one before.” And for that we praise you, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen.

1 Comment

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Now Available! Wild Things & Castles in the Sky | Little Book, Big Story - […] Matthew Clark read his essay on his own podcast, One Thousand Words (that one’s worth subscribing […]

This episode kept me company in the kitchen while preparing dinner; mashing potatoes and creating a bubbly gravy for tender beef.

When a spice was mentioned in your essay, I eagerly reached into my cupboard and opening the lid of the whole nutmeg seed jar, smiled _in delight_ and understood that moment more fully.

Thank you for all you shared here. My children & I have not not yet read any MacDonald, and I am going to add Wee Sir Gibbie to our Read-Aloud list. My older child has just been introduced to the world of Narnia, and is entranced. The book you are featuring in this podcast episode sounds like a rich resource…and I will spread the word about in my homeschool circles. Thank you again for your work! (Now it’s time to eat!)